From the National Association of Realtors:

NAR Economist: ‘Housing Recession Is Over’

Contract signings picked up the pace last month, and home buyers are increasingly facing multiple offer situations. NAR releases its housing forecast for the remainder of the year and 2024.

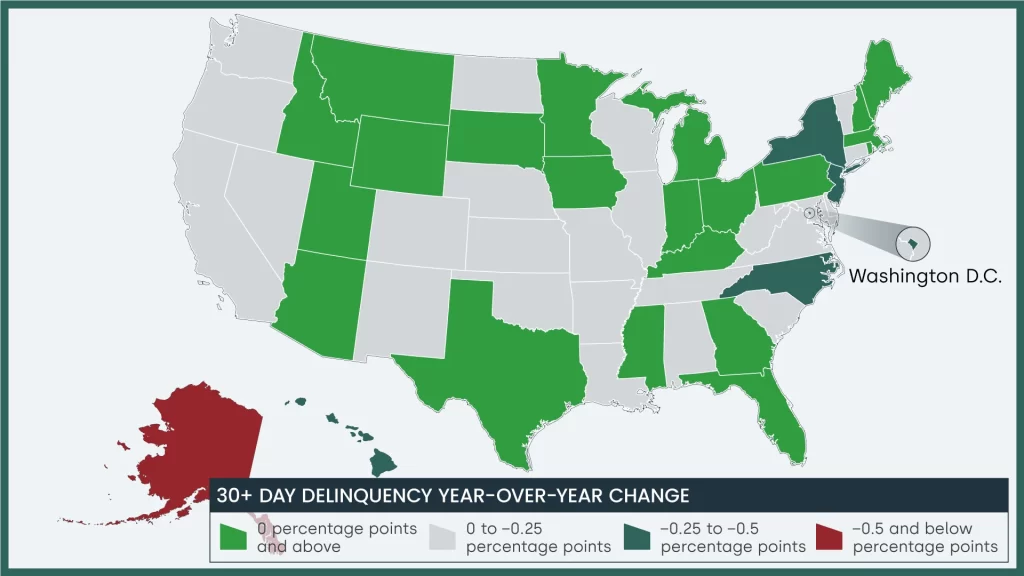

Pending home sales rose slightly in June, and the latest indicators are showing a housing market on the mend. Median existing-home sales prices in June soared to their second highest on record in the last two decades, and more buyers are facing multiple offer situations once again, the latest reports from the National Association of REALTORS® shows. NAR’s Pending Home Sales Index—a forward-looking indicator of home sales based on contract signings—rose 0.3% in June, the first increase in four months.

“The recovery has not taken place, but the housing recession is over,” says Lawrence Yun, NAR’s chief economist. “The presence of multiple offers implies that housing demand is not being satisfied due to a lack of supply. Homebuilders are ramping up production and hiring workers.”

Housing inventories remain at historical lows, down 13.6% from even last year’s low levels. “There are simply not enough homes for sale,” Yun said in a recent report. Seventy-six percent of existing homes sold in June were on the market for less than a month, NAR’s data shows.

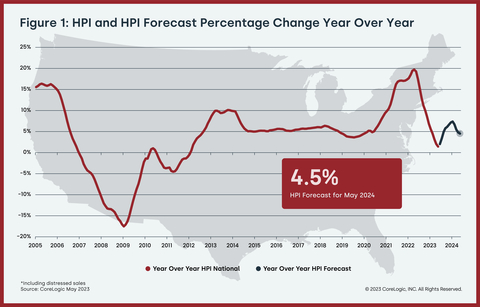

Home buyers are faced with limited choices, higher home prices and higher mortgage rates. But they may find some relief soon: Mortgage rate increases may be mostly over, and that would bode well for home-buying, Yun says.

“With consumer price inflation calming close to the Federal Reserve’s desired conditions, mortgage rates look to have topped out,” Yun says. “Given the ongoing job additions, any meaningful decline in mortgage rates could lead to a rush of buyers later in the year and into the next.”

NAR forecasts that the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage could reach 6.4% by the end of the year, followed by 6% in 2024. Over recent weeks, mortgage rates have been nearing 7%, far from their ultra-low 2% or 3% averages just over a year ago.